The Warlord Era (1916-27) was a period when national authority in China disintegrated and the country broke apart into a jigsaw of regions, each controlled by powerful local leaders. Warlordism was to some extent a culmination of internal divisions that emerged in late Qing China. As Qing authority waned, local leaders moved to increase their own power. This fragmentation of political power continued during Yuan Shikai’s presidency. When Shikai attempted to revive the Qing monarchy and reposition himself as emperor, provincial leaders lost what little faith they had the republican national government. When Shikai died without an obvious successor in 1916, China collapsed into divided warlordism. It remained like this until 1927, when much of the country was reunified by Jiang Jieshi and his National Revolutionary Army. The Warlord Era was a period of uncertainty, disorder and conflict that produced very few if any benefits for ordinary Chinese.

The collapse into warlordism was not surprising, given China’s history. The country’s great size, population, geographical variations and diversity made centralised national government a difficult prospect. This was true even for strong dynasties, however by the late 1800s the Qing was far from strong. The last 20 years of Qing rule produced a steady decline towards decentralisation and provincialism. Local leaders and groups, often encouraged and backed by foreign imperialists, exerted influence and control in their regions. Qing authority and culture remained strong around Beijing and in the north-east of China – but in British-influenced Guangdong, the mountainous regions of central China or on the Tibetan plateau, local leaders became of equal or greater importance than the national government. The late Qing reforms (1901-1910) tried to create a constitutional framework that would strengthen the national government but these reforms failed.

China’s political disintegration was accelerated by the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the failed republican government of 1912-16. The Xinhai or 1911 Revolution threatened the Qing and instigated the rise of two competing governments. In the north, Beiyang Army commander Yuan Shikai emerged as the strongman of the Chinese Revolution, the only leader with enough military clout to force out the Qing. In the south, nationalists led by Sun Yixian formed a provisional government with some legitimacy but no means of enforcing it. Shikai’s control of the military gave him a pathway to the national presidency, though he had little interest in republicanism. Shikai represented more of the old regime than the new, however, his command over the military held China together and allowed for the continuation of national government. While Shikai sat in the president’s chair, provincial warlords did little to challenge his government, fearing military retaliation. That Shikai’s power was derived from military strength has led some to dub him the “father of the warlords” or the “first warlord”.

“The widespread disorder and violence of the war-lord period disrupted foreign trade as well as endangering foreigners. At the same time, the impotence of the central government during the warlord years served as an open invitation to foreigners to fish in China’s troubled waters. Foreign influence occurred in several ways and at several levels, but the two most important involved further control over China’s economic resources and supplying aid to selected warlords. Japan was by far the worst offender in using warlord disunity to force new concessions from China. The other powers were satisfied to wring the maximum profit from the privileges already permitted under treaties from the Qing era.”

James E. Sheridan, historian

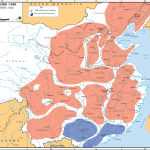

When Yuan Shikai died in June 1916 it created a national power vacuum that was quickly filled by the warlords. Now leaderless, the national army itself broke apart, its regiments or divisions falling under the control of powerful provincial leaders, who claimed them as private armies. Nowhere was this process more visible than in northern China. Yuan Shikai’s Beiyang Army quickly disintegrated and its personnel were swallowed up by three competing warlord factions: the Zhili clique (led by Feng Guozhang), the Anhui clique (Duan Qirui) and the Fengtian clique (Zhang Zuolin). Warlords sought to increase their power by increasing the size of their armies. This was occasionally done by conscription or coercion but usually through enticement. Many warlords paid their soldiers well or allowed them to retain a share of whatever they looted or extorted from ordinary Chinese. In rural areas ravaged by poverty, ‘taking up with the bandits’ became an attractive career option, particularly for young single men. According to historian Hsi-Sheng Chi this economic desperation fuelled a rapid growth in the size of warlord armies: from around 500,000 in late 1916 to more than one million in 1918 and two million in 1928.

It is difficult to form general conclusions about China’s warlords: they were a diverse group with different qualities, methods, attitudes and objectives. Several warlords were former officers in the Qing military; others were provincialists or outsiders who had never belonged the Qing establishment. Some were traditionalists who clung to dynastic and Confucian ideals; others were progressives who recognised the fundamental changes taking place in China. Some of the stronger warlords fancied themselves as potential ‘unifiers’, hoping to conquer enough territory to restore a national government – with themselves as emperor or president, of course. Apart from their use of military force, the most common goal shared by warlords was to make themselves rich. The exploitation, corruption and banditry that flourished under warlordism had dire effects on the ordinary people. Warlords printed excessive amounts of paper money to fund their armies, leading to high inflation. They seized control of government infrastructure and privately-owned businesses. They imposed new taxes and raised existing ones (in one warlord province land tax increased fivefold). Aware of its profitability, many warlords also revived the trade in opium, compelling farmers to grow it and encouraging its open sale. The private armies of warlords were often a law unto themselves, behaving recklessly, harassing and assaulting locals and stealing or destroying their property.

Not all warlords were driven entirely by greed. A handful behaved like benevolent dictators, their leadership based on political pragmatism and some concern for the people they ruled. One of these was Yan Xishan (Wade-Giles: Yen Hsi-Shan) who ruled in Shanxi province. Yan was well educated, a career soldier in the Qing military and a former advocate of Self-Strengthening. Unlike other warlords, he focused on improving and modernising Shanxi, rather than expanding territory or amassing a personal fortune. Yan entered into alliances to keep Shanxi out of conflict with other warlords, while introducing social reforms, like the abolition of foot binding and improvements to girls’ education. Feng Yuxian, a northern warlord who later captured Beijing and aligned with the Guomindang, outlawed foot binding, prostitution and opium trafficking in areas under his command. He also encouraged his soldiers to convert to Christianity, sometimes ‘baptising’ entire companies of men with a fire hose.

During the Warlord Era a national government continued in Beijing, however, it did was not representative and exerted no national control. The Beiyang government, as it was known, presented as a civilian parliamentary government. In reality, it was a front for the dominant warlord or warlord faction in Beijing. Control of the capital was a financial bonanza for warlords. The Beiyang government, despite its illegitimacy, was still recognised by foreign powers. Foreign merchants continued to make massive payments for duties and import taxes, money that went to local warlords. This revenue made Beijing and its surrounds a rich prize for competing warlord factions, who warred constantly over the capital. In 1920 the Zhili and Anhui cliques fought a brief but bloody war over Beijing, the Zhili warlords emerging victorious. In mid-1922 the Zhili faction defended Beijing from an attempted takeover by the northern Fengtian clique. The Fengtian warlords, led by Zhang Zuolin, reassembled and returned in September 1924, expelling the Zhili and seizing control of the Beiyang government. These constant struggles made the Beiyang government changeable and unstable: it had seven different heads of state and more than two dozen different ministries between 1916 and 1928.

The warlord period was one of political division, instability, corruption and self-interest, economic stagnation and social repression. While some warlords formed ties with wealthy business elites, the uncertainty and instability of the period were not conducive to economic progress or the development of new industries. A handful of warlords attempted social reform but none that entailed significant investment or innovation. There were few sincere and meaningful attempts to improve the lives of ordinary people. The majority of Chinese, particularly the rural peasantry, suffered more under the warlords than they had under the Qing. Large numbers of peasants were driven from their land, which was often parcelled off to private soldiers. By 1925 the number of unemployed in China was estimated at more than 168 million, more than half of them peasants and farm labourers. By this stage, Sun Yixian’s nationalists and their new-found allies, the Moscow Comintern and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), were planning the end of warlordism. From their stronghold in the southern province of Guangdong, the Guomindang and its military arm, the National Revolutionary Army, were preparing to move against the warlords and reunite China by force.

1. The Warlord Era was a period of political fragmentation and regional militarism in China, beginning with the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916 and ending in 1927.

2. Warlordism was caused in part by growing provincial power in the last half-century of Qing rule, the emergence of powerful local leaders and the failure of republican government under Shikai.

3. The warlords and warlord factions used private or provincial armies to exert and expand their control. Most warlords and warlord soldiers were motivated by economic greed.

4. A few warlords were progressive minded and attempted social reforms. In general terms, however, the lives of Chinese peasants was noticeably worse under warlordism than it had been under the Qing.

5. A national government operated in Beijing during the Warlord Era and profited from foreign trade, duties and taxes. This government was controlled by warlords and was neither truly representative or legitimate.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glenn Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Warlord Era“, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/warlord-era/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.